The case was notable for a number of reasons; the bravery of the victim, the leniency of the six month sentence imposed by the judge (prosecutors had asked for six years, already down from 14 years), and as it instigated a much needed public discussion about our collective response to sexual assault and the media 'framing' of such crimes.

|

| The rapist was good at swimming? This is clearly relevant information! |

Personally, details of the case seemed dispiritingly familiar. About seven years ago, I served on a jury for a rape case, and there were lots of worrying similarities between what happened at Stanford and what I saw during the trial I served on.

Essentially, the basic version of events was this: a young woman had met up with friends in an apartment, and gone for drinks in town. She had later gone back to the apartment to sleep, where she was raped by a mutual acquaintance. She woke up, the attacked fled, and she called the police. To me, it seemed like a fairly open and shut case, and the law itself is fairly decisive on the matter; lack of consent can be demonstrated by "Evidence that by reason of drink, drugs, sleep...the complainant was unaware of what was occurring and/or incapable of giving valid consent"

The trial itself was an eye-opening experience. The defendant pleaded not guilty, and had a very forceful lawyer who doggedly challenged almost every aspect of the prosecution. There were many parallels with the current Stanford case. The defense posited that the victim was drunk; she had been 'flirty' with the defendant and worn provocative clothing; she had not explicitly said 'yes' but had consented with her body language. These seemed flimsy excuses, but perhaps the most worrying was the insinuation that the victim had accused her attacker of rape because she 'regretted' having consensual sex with him and was worried about her reputation.

|

| When has that ever happened? |

I realise this is the job of a defence lawyer, and that every accused person has the right to a thorough defence. But the constant attacks on the credibility of the victim were unedifying given the strength of evidence. Like the Stanford victim, the defense looked exceedingly hard for minor inconsistencies that they hoped would discredit the witness. Every word of testimony was picked over in detail as evidence that she was lying about being raped. "You said in your statement the day after the attack that you had three Bacardi Breezers, but now you are saying that you only had two, is that correct?" This seemed a spurious line of defence, given that there was almost a year between the trial and the date of the attack. Personally, I often can't remember what I had for lunch yesterday- but I hope that wouldn't undermine my evidence in a trial of a serious offence.

After we had heard several days of testimony and evidence, the jury retired to consider our verdict. What was shocking to me was that even though the evidence I had heard seemed damning, the majority of the jury were in favour of a not-guilty verdict. There were doubts as to whether the evidence was "beyond reasonable doubt", as essentially it was the statement of the victim versus that of the accused. It seemed as though they hadn't questioned why the victim would consent only to violently change her mind after a minute. I believe that they had been deceived for the defence, which had constantly cast false aspersions, seeded doubt, and basically made it feel as though a guilty verdict was impossible. The first time we were called back by the judge, the jury was split about 9-3 in favour of not-guilty.

We returned to court the next day. We discussed it some more. Again, we were called back. We still didn't have a unanimous decision, and the judge said he would accept an 11-1 decision. After another hour, we came back with a verdict: guilty.

It felt like the right decision, and justice had been served. However, many victims never get that opportunity.

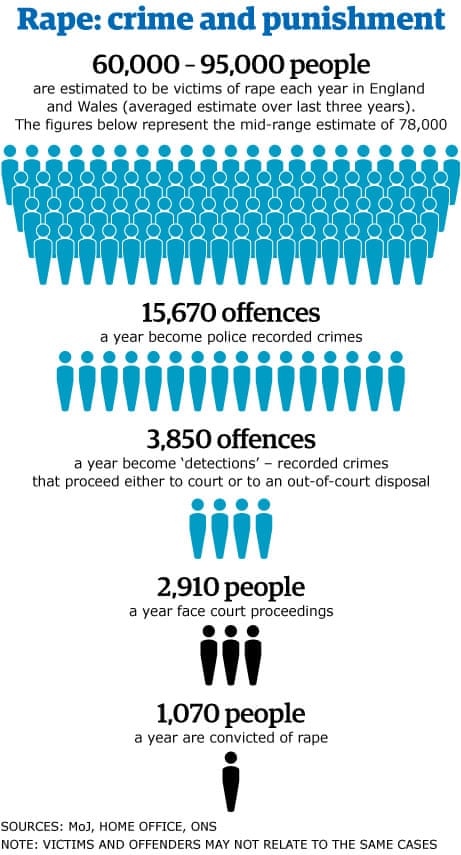

Only a minority of offences are reported to the police. Only a minority of those are picked up by the Crown Prosecution Service. Only a minority of those result in a guilty verdict. The barriers to a successful prosecution mean that the odds are overwhelming stacked in favour of perpetrators instead of victims. Imagine if we only had a similar conviction rate for murderers- what would the public response be?

In many ways, numbers are only a fraction of the story. The statistics alone- depressing though they may be- still don't tell the full picture; they're numbers on a page. They can't express the humanity of the victims: the indignities of a police rape exam, the trauma and fear which persists long after an attack, having your testimony and reputation dragged through the mud in a courtroom. That was why the statement of the victim in the Stanford case was important; it humanised a problem which is so often lost in dispiriting numbers. By staying anonymous, she's given a voice to all the silent victims.

Nevertheless, the public attention given to what happened on at Stanford should not obscure the fact that collectively, we have a societal problem with rape. Sexual offences are still ignored, overlooked, or otherwise dismissed as a minority 'feminist' issue.

|

| Fair. |

We all have to bear some responsibility for a culture which allows rapists to evade justice. We all need to educate our sons on the importance of consent and respect, instead of just warning our daughters to 'be careful out there'. We all have a responsibility.to change the system.

No comments:

Post a Comment